Manu as a weapon against egalitarianism:

Nietzsche and Hindu political philosophy

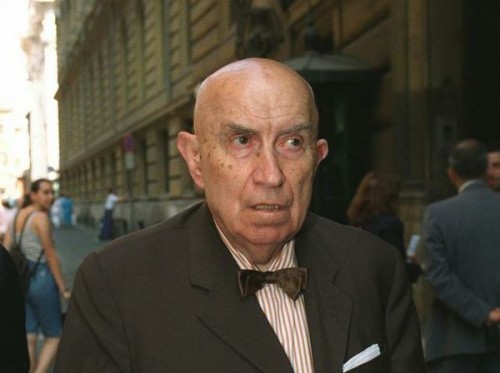

Dr. Koenraad Elst

Introduction

Friedrich Nietzsche greatly preferred the ‘healthier, higher, wider world’ of the Hindu social code Mânava-Dharma-Shâstra (‘Code of Human Ethics’), also known as Manu-Smrti (‘Manu’s Classic’), to ‘the Christian sick-house and dungeon atmosphere’ (TI Improvers 3). We want to raise two questions about his eager use of this ancient text:

Firstly, a question of historical fact, viz. how correct was Nietzsche’s understanding of the text and the society it tried to regulate? The translation used by him suffers from some significant philological flaws as well as from interpretative bias, to which he added an agenda-driven reading of his own.

Secondly, to what extent did Nietzsche’s understanding of Hindu society play a role in his socio-political views? At first sight, its importance is quite limited, viz. as just an extra illustration of pre-Christian civilization favoured by him, as principally represented by Greece. Crucial pieces of Manu’s worldview, such as the centrality of a priestly Brahmin class and the notion of ritual purity, seem irrelevant to or in contradiction with Nietzsche’s essentially modern philosophical anthropology. To others he didn’t pay due attention, e.g. Manu’s respect for asceticism as a positive force in society, seemingly so in conflict with the Nietzschean contempt for ‘otherworldiness’, resonates with subtler pro-ascetic elements in Nietzsche’s conception of the Übermensch. Yet, a few specifically Indian elements did have a wider impact on his worldview, especially the notion of Chandâla (untouchable), to which however he gave an erroneous expansion unrelated to Manu.

1. What is the Manu-Smrti?

Friedrich Nietzsche greatly preferred the ‘healthier, higher, wider world’ of the Hindu social code Mânava-Dharma-Shâstra, the ‘Textbook of Human Ethics’, also known as Manu-Smrti, ‘Manu’s Classic’, to what he called ‘the Christian sick-house and dungeon atmosphere’ (TI Improvers 3). In a letter to his friend Peter Gast, he wrote:

This absolutely Aryan testimony, a priestly codex of morality based on the Vedas, of a presentation of caste and of ancient provenance – not pessimistic eventhough priestly – completes my conceptions of religion in the most remarkable manner. (KSA 14.420)

To his mind, the contrast between Manu’s classic and the Bible was so diametrical that ‘mentioning it in one breath with the Bible would be a sin against the spirit’ (AC 56). So, at first sight, he was very enthusiastic about this founding text of caste doctrine, though we shall have to qualify that impression. We want to raise two questions about his use of this ancient text, one of historical accuracy and one of the meaning Nietzsche accorded to this acknowledged source of inspiration in his view of society. But first of all, a few data about the Manu-Smrti must necessarily be stated before we can understand what role it could play in Friedrich Nietzsche’s thinking.

1.1. Manu, the patriarch

There is no indication that Nietzsche had much of an idea about who this Manu was after whom India’s ancient ethical code had been named. In Hindu tradition as related in the Veda and in the Itihâsa-Purâna literature (‘history’, comparable to Homer or to the Sagas, and ‘antiquities’, i.e. mythohistory comparable to Hesiod or the Edda), Manu was, through his numerous sons, the ancestor of all the known pre-Buddhist Indian dynasties. He himself is often described as a ‘son of Brahma’, though his full name, Manu Vaivasvata, implies that he was one of the ten surviving sons of Vivasvat, himself a son of Sûrya, the sun.

During the Flood, Manu had led a party of survivors by boat up the Gangâ to the foothills of the Himâlaya, then founded his capital in Ayodhyâ. His son Ikshvâku founded the ‘solar dynasty’ which retained the city of Ayodhyâ. Ikshvâku’s descendent Râma, hero of the Râmâyana epic, ruled there. The Buddha belonged to a minor branch of the same lineage, the Shakya clan which was so jealous of its noble ancestry that it practised the strictest endogamy. The later Gupta dynasty, presiding over India’s ‘golden age’, likewise claimed to be a branch of the solar dynasty. Another of Manu’s sons, Sudyumna, or alternatively his daughter Ilâ, founded the ‘lunar dynasty’ with capital at the Gangâ-Yamunâ confluence in Prayâga. His descendent Yayâti established himself to the west in the Saraswatî basin, present-day Haryânâ, where his five sons founded the ‘five nations’, the ethnic horizon of the Vedas.

Yayâti’s anointed heir was Puru, whose Paurava nation was to compose the Rg-Veda, the foundational collection of hymns to the gods. The Vedic age started with the Paurava king Bharata, after whom India has been named Bhâratavarsha or just Bhârat (as on India’s post stamps). In his clan, dozens of generations later, an internal quarrel developed into a full-scale war, the subject-matter of the Mahâbhârata, the ‘great (epic) of the Bhârata-s’. A key role in this war, which marked the end of the Vedic age, was played by the fighting brothers’ distant cousin Krishna, a descendent of Yayâti’s son Yadu. Yet another son of Yayâti’s, Anu, is said to be the ancestor of the Asura-worshippers, i.e. the Iranians, who were at times the enemies of the Deva-worshipping Vedic people..

So, Manu is known as the ancestor of all the Ârya people (vide §1.2), preceding all the quasi-historical events reported in Sanskrit literature. The account by Seleucid Greek ambassador Megasthenes of Hindu royal genealogy, where Manu is identified with Dionysos, times his enthronement at 6776 BC (Arrian: Indica 9.9, Pliny: Naturalis Historia 6.59, in Majumdar 1960 223 and 340), an intractable point of chronology that we must leave undecided for now.

The Vedic seers repeatedly call Manu ‘father’ (1.80.16, 1.114.2, 8.63.1) and ‘our father’ (2.33.13), and otherwise mention him over a hundred times. They pray to the gods: ‘May you not lead us far from the ancestral path of Manu’ (8.30.3). They address the fire-god Agni thus: ‘Manu established you as a light for the people’ (1.36.19). The Vedic worship of ‘33 great gods’ (often mistranslated as ‘330,000,000 gods’, koti meaning ‘great’ but later acquiring the mathematical sense of ‘ten million’), mostly enumerated as earth, heaven, eight earthly, eleven atmospheric and twelve heavenly gods, is said to have been instituted by Manu (8.30.2). Moreover, one common term for ‘human being’ is manushya, ‘progeny of Manu’.

Because of his name’s prestige, the ancient patriarch is also anachronistically credited with the authorship of the Manu-Smrti (‘Manu’s Recollection-Classic’) or Mânava-Dharma-Shâstra (translatable as both ‘Manu’s Ethical Code’ and ‘Human Ethical Code’), a text edited from slightly older versions in probably the 1st century CE. Friedrich Nietzsche exclusively refers to Manu as the author of the Mânava-Dharma-Shâstra, seemingly unaware of his legendary status as the progenitor of the Ârya-s.

1.2. The Code of the Ârya-s

For at least two thousand years, the word Ârya has meant: ‘noble’, ‘gentleman’, ‘civilized’, and in particular ‘member of the Vedic civilization’. The Manu Smrti uses it in this sense and emphatically not in either of the two meanings which ‘Aryan’ received in 19th century Europe, viz. the linguistic sense of ‘Indo-European’ and the racial sense of ‘white’ or ‘Nordic’. Thus, MS 10.45 says that those outside the caste system, ‘whether they speak barbarian languages or Ârya languages, are regarded as aliens’, indicating that some people spoke the same language as the Ârya-s but didn’t have their status of Ârya. As for race, the Manu Smrti (10.43f.) claims that the Greeks and the Chinese had originally been Ârya-s too but that they had lapsed from Ârya standards and therefore lost the status of Ârya. So, non-Indians and non-whites could be Ârya, on condition of observing certain cultural standards, viz. those laid down in the MS itself. The term Ârya was culturally defined: conforming to Vedic tradition.

But at least in the two millennia since the Manu Smrti, the only ones fulfilling this requirement of living by Vedic norms were Indians. When, during India’s freedom struggle, philosopher and freedom fighter Sri Aurobindo Ghose (1872-1950) wrote in English about ‘the Aryan race’, he meant very precisely ‘the Hindu nation’, nothing else. In 1914-21, together with a French-Jewish admirer, Mirra Richard-Alfassa, he also published a monthly devoted to the cause of India’s self-rediscovery and emancipation, the Ârya. In 1875, a socially progressive but religiously fundamentalist movement (‘back to the Vedas’, i.e. before the ‘degeneracy’ of the ‘casteist’ Shâstra-s and the ‘superstitious’ mythopoetic Purâna-s) had been founded under the name Ârya Samâj, in effect the ‘Vedicist society’. If the word Ârya had not become tainted by the colonial and racist use of its Europeanized form Aryan/Arier, chances are that by now it would have replaced the word Hindu (which many Hindus resent as a Persian exonym unknown to Hindu scripture) as the standard term of Hindu self-reference.

Against the association of the anglicised form ‘Aryan’ with colonial and Nazi racism, modern Hindus always insist that the term only means ‘Vedic’ or ‘noble’ and has no racial or ethnic connotation. This purely moral, non-ethnic meaning is in evidence in the Buddhist notions of the ‘four noble truths’ (chatvâri-ârya-satyâni) and the ‘noble eightfold path’ (ârya-ashtângika-mârga). So, the meaning ‘noble’ applies for recent centuries and as far back as the Buddha’s age (ca.500 BC), but not for the Vedic age (beyond 1000 BC), especially its earliest phase. Back then, against a background of struggle between the Vedic Indians and the proto-Iranian tribes, the Dâsa-s and Dasyu-s, we see the Indians referring to themselves, but not to the Iranians, as Ârya; and conversely, the Iranians referring to themselves, but not to the Indians, as Airya (whence Airyânâm Xshathra, ‘empire of the Aryans’, i.e. Iran). And if we look more closely, we see the Vedic Indians, i.e. the Paurava nation, refer to themselves but not to other Indians as Ârya. So at that point it did have a self-referential ethnic meaning (Talageri 2000 154 ff.).

Possibly this can be explained with the etymology of the word, but this is still heavily under dispute. Köbler (2000 48 ff.) gives a range of possibilities. It has been analysed as stemming from the root *ar-, ‘plough, cultivate’ (cfr. Latin arare, aratrum), which would make them the sedentary people as opposed to the nomads and hunter-gatherers; and lends itself to a figurative meaning of ‘cultivated, civilized’. Or from a root *ar-, ‘to fit; orderly, correct’ (cfr. Greek artios, ‘fitting, perfect’) and hence ‘skilled, able’ (cfr. Latin ars, ‘art, dexterity’; Greek arête, ‘virtue’, aristos, ‘best’), which may in turn be the same root as in the central Vedic concept rta, ‘order, regularity’, whence rtu, ‘season’ (cfr. Greek ham-artè, ‘at the same time’). Or from a root *ar, ‘possess, acquire, share’ (cfr. Greek aresthai, ‘acquire’), an interpretation beloved of Marxist scholars who interpret the Ârya class as the owner class. Or, surprisingly, from a root *al-, ‘other’ (cfr. Greek allos and Latin alius, ‘other’), hence ‘inclined towards the other/stranger’, hence ‘hospitable’, like in the name of the god Aryaman, whose attribute is hospitality. It is the latter sense from which the ethnic meaning is tentatively derived: ‘we, the hospitable ones’, ‘we, your hosts’, hence ‘we, the lords of this country’. The linguists are far from reaching a consensus on this, and for now, we must leave it as speculative.

At any rate, the form Ârya, though probably indirectly related with words in European languages, exists as such only in the Indo-Iranian branch of the Indo-European language family. The common belief that Eire as ethnonym of the westernmost branch of the Indo-European speech community is equivalent with Ârya, is etymologically incorrect, as is the eager linkage of either with German Ehre, ‘honour’. This is one reason why the use of the English word ‘Aryan’ for the whole Indo-European language family was misconceived and has rightly been abandoned.

The main point for now is that the legendary Manu was the patriarch and founder of Vedic or Ârya civilization. His name carried an aura, so the naming of a far more recent book after him was merely a classic attempt to confer more authority on the book. The name of the book’s real author or final editor is unknown, but he must have lived at the very beginning of the Christian age. Older versions of the Dharma-Shâstra-s have been referred to in the literature of the preceding centuries, citing injunctions no longer extant in the classical versions. This confirms to us moderns, though not to the disappearing breed of traditionalist Hindus, that the law codes including Manu’s are products of history, moments in a continuous evolution, rather than an immutable divine law laid down at the time of creation.

1.3. Is the Manu Smrti a law book?

In 1794, Bengal Supreme Court judge Sir William Jones (1746-94), discoverer or at least herald of the kinship of the Indo-European languages in 1786, translated the Manu Smrti in English. Soon the British East India Company made the Manu Smrti the basis of the Code of Hindu Law in its domains, parallel with the Shari’a for Muslim Law. Colonial practice was to avoid trouble with the natives by respecting their customs, so British or British-appointed judges consulted the MS to decide in disputes between Hindus. But this was the first time in history that the book had any force of law.

It is an important feature of the Manu Smrti that it explicitly recognizes that laws are changeable. That doesn’t mean that anything goes, for the right to amend the laws is strictly confined to Brahmins well-versed in the existing law codes (12.108), so that they will preserve the spirit of the law even while changing its letter. Nonetheless, this provision for change helps to explain why Hindus have been far more receptive to social reform than their Muslim compatriots, for whom Islamic law is a ‘seamless garment’: pull out one thread and the whole fabric comes apart. On the other hand, this openness to reform never led to serious changes in social practice until the pressure from outside became immense, viz. under British colonial rule with its modernizing impact. But at least the principle that the Manu Smrti was perfectible and changeable was understood from the start and is implied in its classification as a Smrti, a man-made ‘memorized text’ or ‘classic’, or Shâstra, a man-made ‘rule book’, in contrast with the Shruti literature (‘glory’, often mistranslated as ‘heard text’ in the sense of ‘divinely revealed text’, like the Qur’ân), i.e. the Vedas, which had by then been exalted to divine status, and which don’t have the character of rule books but of hymns addressed to the gods.

Manu (as we shall call the anonymous author) explicitly acknowledges the validity of customary law: ‘He must consider as law that which the people’s religion sanctions’ (7:203). Much of what he describes was nothing but existing practice. Until the enactment of modern laws by the British and the incipient Indian republic, the final authority for intra-caste disputes was the caste pañchâyat (‘council of five’), for inter-caste disputes the village pañchâyat, in which each local caste was represented and had a veto right. These councils were sovereign and not formally bound by the Manu Smrti or any other Shâstra-s, though these could be cited in the deliberations by way of advice.

Apart from Manu’s own Shâstra, there were quite a few rival texts written with the same purpose. In anti-Hindu polemics arguing for the utter inhumanity of the caste system, Manu is often accused of laying down the rule that ‘if an untouchable listens attentively to Veda recitation, molten lead must be poured into his ears’ (because his unclean person would pollute the Vedic vibration, with detrimental consequences for the whole of society…). This rule is nowhere to be found in Manu. Yet it is authentic, but it is from the less prestigious Gautama-Dharma-Sûtra (12.4). The most famous Dharma-Shâstra apart from Manu’s is probably the one credited to Yajñavalkya, the Vedic philosopher who introduced the crucial notion of the Self (âtman) in the Brhadâranyakopanishad. But here again, the extant text, more streamlined and contradiction-free than Manu’s, is a number of centuries younger than its purported author.

Though not law books stricto sensu, these Shâstra-s (presented exhaustively in Kane 1930 ff.) do communicate a legal philosophy and directive principles for how people should conduct themselves in society and how rulers should organize it. Their most striking feature when compared with modern law, though not dissimilar to most pre-modern law systems even in West Asia and Europe, is that they allot different rights, prohibitions and punishments to different classes of people. In particular, and to Nietzsche’s great enthusiasm, it thinks of the social order in terms of the varna-vyavasthâ, approximatively translated as the ‘caste system’.

Thus, the murder of a Brahmin is punished more heavily than the murder of a low-caste person. For theft, a high-caste person received a heavier punishment than a low-caste person (Gopal 1959 190). And in a rule to which Friedrich Nietzsche alludes (14[176] 13.362), a labourer is not punished for drunkenness, but a Brahmin is, because according to Nietzsche, ‘drunkenness makes him sink to the level of the Shudra’. From the Hindu viewpoint, the rationale for the latter rule was more probably that a drunken Brahmin might desecrate the Vedas by reciting them in a jocular or mocking manner, which would be highly inauspicious, whereas a labourer’s loss of self-control is less consequential. So, while Manu is unabashedly non-egalitarian, Nietzsche overdoes this focus on inequality because he doesn’t empathize with other, religious considerations that were crucial to Manu.

In Manu’s view, everyone has to do his swadharma, ‘own duty’, which implies distinctive rules as well as privileges. This is not conceived in an individualistic sense (as in Nietzsche’s Zarathustra calling to ‘walk the one road no one can walk but you’) but as one’s caste duty. It is mostly because of its casteism that the Manu-Smrti is abhorred by Indian and Western egalitarians, and that it was admired by pro-aristocratic thinkers such as Nietzsche.

1.4. Reconciling Vedic theory with Hindu practice

In his letter to Peter Gast of 31 May 1888, Nietzsche called the Manu-Smrti ‘a priestly codex of morality based on the Vedas’ (KSA 14.420). Manu’s understanding of ‘Vedic’, like that of modern Hindus, and like Nietzsche’s borrowed idea, is not certified by scholars as historically Vedic. More than a thousand years had elapsed between the final edition of the Vedas and the composition of the Manu-Smrti, and society had evolved considerably. One of Manu’s self-imposed tasks was to offer justification from the Veda-s, then already an old and little-understood corpus, for the mores and social ideals of his own day.

Nietzsche thought these ancient laws, Manu’s as much as Moses’, were endowed with authority through the pious lie of divine sanction. In fact, Manu does not claim a divine origin for his code the way Moses did, but the distinction is only technical; the attribution of the MS to the ancient patriarch and the mere fact of its use of the sacred Sanskrit language gave it a religious aura. Manu was a great trend-setter for the later and current Hindu tendency to back-project all later Hindu practices (e.g. idol-worship, astrology) and beliefs (e.g. in reincarnation, inviolability of the cow) unhistorically onto the Vedas. In particular, Manu’s account of caste relations has no precedent in the Vedic corpus, which apparently reflects the simpler social structure of a simpler age.

The Rg-Veda, and then only its youngest book, mentions the four varna-s (castes) as springing from the different body-parts of the Cosmic Man: the Brâhmana from his face, the Kshatriya from his upper body, the Vaishya from his lower body, the Shûdra from his feet (RV 10.90.12). It is thus literally a corporatist explanation of society, with the social classes united in purpose as the limbs of a single body, similar to the corporatism found in Titus Livius’ account of Menenius Agrippa’s speech against class struggle, and in Saint Paul (1 Corinthians 12). This founding text is of course quoted approvingly by Manu (1:93).

However, the Rg-Veda doesn’t yet mention the really operative units of Hindu society, the thousands of jâti-s, or endogamous groups. Nor does it link the varna-s to hereditary profession, another important feature of caste. It is merely stated that these four functions exist in late-Vedic society, as they do in most developed societies. Presumably, just as the relation between the sexes was demonstrably more flexible in the Vedic as compared with the classical Hindu period (Altekar 1959), the relations between the social strata was likewise not as rigid yet. The Manu Smrti marks the phase of crystallization of the system of caste segregation.

The notion of inborn ritual uncleanness or untouchability (asprshyatâ) doesn’t figure in the Rg-Veda either. That is why modern Hindu social reformers could appeal to the Rg-Veda as scriptural justification for abolishing untouchability. The first apparent mention of untouchables is probably in the Chândogya Upanishad (5.3-10), where the Brahmins Uddâlaka Gautama Aruni and his son Shvetaketu find that they don’t know the answer to questions about life after death on which a prince has quizzed them. They go to the king who tells them that his own Kshatriya caste wields power thanks to the secret knowledge which until then they never shared with the Brahmins, viz. that man reincarnates. At once he adds the retributive understanding of reincarnation: ‘Those who are of pleasant conduct here, the prospect is, indeed, that they will enter a pleasant womb, either the womb of a Brahmin, the womb of a Kshatriya, or the womb of a Vaishya. But those who are of stinking conduct here, the prospect is, indeed, that they will enter a stinking womb, either the womb of a dog, or the womb of a swine, or the womb of a Chandâla’ (5.10.7).

In theory, the meaning of Chandâla in this early context is open, it could be an ethnonym for some feared or despised foreign tribe (arguably the Kandaloi mentioned in Ptolemy’s Treatise on Geography 7.1.66) which got incorporated only later as a lowly caste. However, the term’s appearance in contrast with the explicitly named upper castes indicates that it already refers to an unclean or untouchable caste. By Manu’s time, the Chandâla’s or ‘fierce’ untouchables (possibly a folk etymology for what was originally a non-Sanskritic ethnonym) were an established feature of Hindu society. They were also called avarna, ‘colourless’, ‘without caste pride’. But it would be wrong to translate this as ‘casteless’, for they too live in endogamous jâti communities.

Nowadays, jâti is often infelicitously translated as ‘subcaste’, but ‘caste’ would be more accurate, i.e. endogamous group. The British colonizers initially translated this term as ‘tribe’ (as in ‘the Brahmin tribe’), which inadvertently held the key to the jâti-s’ historical origin. As a general rule, jâti-s originated as independent tribes that got integrated into the expanding Vedic society, whose heartland was limited to the region around present-day Delhi. It was part of the Brahminical genius to let them keep or even strengthen their separate identities, founded in their endogamy, all while ‘sanskritizing’ them, i.e. bringing them into the Vedic ritual order (somewhat like the Catholic Church facilitated the christianization of the Pagans in the Roman Empire by integrating some of their customs and institutions). Secondarily, some specific jâti-s originated by division (or, in the modern age, fusion through intermarriage) of pre-existing jâti-s.

The four varna’s were originally not endogamous by definition. They were hereditary, but only through the paternal line, as we see in a number of inter-varna couples in the Vedic literature and the epics. A man could marry a woman from any caste (though preferably not from a higher caste), she would move into his house and his varna community, and their children would naturally become part of their father’s varna. However, intermarriage between varna-s also went out of use, and Manu reports the practice but expresses his disapproval. The effective unit of endogamy was the jâti, not the varna, but since most jâti-s were classified under one of the varna-s, any inter-varna marriage would be an inter-jâti marriage and hence forbidden. While a hypergamous marriage between a higher-born man and a lower-born woman would be frowned upon but often tolerated (though least so in the Brahmin caste), a hypogamous union was strictly out of bounds: ‘If a young girl likes a man of a class higher than her own, the king should not make her pay the slightest fine; but if she unites herself with a man of inferior birth, she should be imprisoned in her house and placed under guard. A man of low origin who makes love to a maiden of high birth deserves a corporal or capital punishment’ (MS 8.365f.).

Hindu reformists often claim that caste was never hereditary, and that the Bhagavad-Gîtâ, the most authoritative source in everyday Hinduism, edited in about the same era as the MS, defines a person’s varna by his guna, ‘quality, aptitude’ and karma, ‘work’ (4.13). But those criteria are not given in opposition to heredity, on the contrary: in terms of work and aptitude, people in pre-modern societies tended to follow in their parents’ footsteps, statistically speaking. Moreover, the Gîtâ itself is explicit enough about the understanding of caste identity as hereditary and implying endogamy. When its hero Arjuna shies away from battle and displays a failing in the martial quality (guna) befitting a warrior, his adviser Krshna does not tell him that by guna he clearly isn’t a Kshatriya and hence free from military duty, but instead tells him to overcome his doubts and do his Kshatriya duty, for regardless of his personal traits he just happens (viz. by birth) to be a member of the Kshatriya caste.

When the two argue opposing positions regarding the justice of waging the fraternal war, they do so with reference to the same concern, viz. the need to avoid varna-sankara, roughly ‘mixing of castes’. Both say that the other’s proposed line of action, viz. fighting c.q. avoiding the war, would lead to the ‘immorality of women’ and thence to breaches of caste endogamy. (BG 1.41-43, 3.24). When in a society two opposing arguments are based on the same value, you know that that value is deeply entrenched in that society,-- i.c. caste as an hereditary communal identity guarded by endogamy.

2. Nietzsche’s understanding of the text

Friedrich Nietzsche didn’t share the enthusiasm for all things Indian evinced by many of his contemporaries. Thinkers critical of Christianity from Voltaire to Arthur Schopenhauer and Ernest Renan had been using the glory of Indian civilization as a counterweight against the ideological influence which Christianity still wielded even among nominal unbelievers. Indology had been arousing a lot of interest in its own right, but was also instrumentalized in Europe’s self-discovery and self-glorification through the study of the Indo-European language family and the presumed civilization underlying its original expansion. Moreover, there was always the titillating element in India’s exotic features, charming or horrifying, such as the much-discussed custom of widows’ self-immolation (satî). All this seems to have left Nietzsche cold. At any rate none of it figures in his published works, except for his references to Manu’s thinking on caste.

The extant literature on the understanding of Manu in Nietzsche’s work is limited in quantity. This is logical, given that Nietzsche’s own discussion of Manu amounts to only a few pages in total. In a short but important paper, Annemarie Etter (1987, further built upon by Berkovitz 2003 and 2006, Smith 2006, Bonfiglio 2006; while Lincoln 1999 101-120 seems to have worked independently on the same theme) draws attention to the poor quality of the Manu Smrti translation which Nietzsche used, viz. the one included in Louis Jacolliot’s book Les Législateurs Religieux: Manou, Moïse, Mahomet (1876), to be discussed here in §2.4. But apart from flaws in the text version used by Nietzsche, there are three more sources of distortion in his understanding of caste society, viz. Manu himself, Jacolliot’s personal additions to his translation of the received text, and Nietzsche himself.

2.1. Errors in Manu

The Manu Smrti is usually referred to, especially by its modern leftist critics in India, as the casteist manifesto pure and simple. This is fair enough in the sense that there is no unjustly disregarded anti-caste element tucked away somewhere in Manu’s vision of society; the text is indeed casteist through and through. However, the scope of the Manu Smrti is broader, dealing with intra-family matters, the punishment of crime, the king’s (in the sense of: the state’s) duties, money-lending and usury, et al. Matters are further complicated by the fact that the text itself contains contradictions, e.g. allowing niyoga or levirate marriage (9.59-63) only to disallow it in the next paragraph (9.64-69, as pointed out by Kane 1930.I.331); recommending meat-eating on certain ceremonial occasions (5.31-41) yet imposing strict vegetarianism elsewhere (5.48-50); describing the father as equal to a hundred Vedic teachers, then reversing this by calling the teacher superior to the father (2.145f.).

Part of the treatise’s self-imposed mission was to reconcile ancient Vedic injunctions, then already obsolete, with social mores actually existing in India around the turn of the Christian era. This seriously muddles Manu’s account of caste, e.g. first allowing a Brahmin man to marry a Shûdra woman (2.16, 3.12f.), as was clearly the case in the Vedic age, then prohibiting the same (3.14-19).

In order to fit the observed reality of numerous jâti-s into the simple Vedic scheme of four varna-s, Manu develops a completely far-fetched theory that each jâti originated from a particular combination of varna-s through inter-varna marriage. This makes no historical or logical sense. In fact, many jâti-s were tribes whose existence as distinct endogamous groups predated the Vedic age, let alone the MS’s age, and even the more recently originated jâti-s didn’t come into being the way Manu suggested.

Manu despises the lowest jâti-s not on account of race, nor ostensibly because of unclean occupations, but because they were born from sinful unions. Most of all he condemns the marriage uniting people from the varna-s at opposing ends of the varna hierarchy and thus most contrary to the ideal of varna endogamy. Not always consistently, but the general thrust of his teaching on endogamy is clear enough. And as if in punishment for their parents’ sins, the children of inter-caste unions became the people performing the lowliest and most unclean tasks.

The Dharma-Shâstra–s give a completely far-fetched theory of the origins of the castes, e.g. the Gautama-Dharma-Shâstra (4.17) relays the view that the union of a Shûdra woman with a Brâhmana, a Kshatriya or a Vaishya man brings forth the Pârashava c.q. the Yavana (‘Ionian’, Greek or West-Asian) and the Karana jâti. Likewise, Manu claims that ‘the Chandâla-s, the worst of men’ are the progeny of a servant father and a priestly mother (10.12). Clearly, the Chandâla-s were looked down upon already, mainly because of their unclean labour (any work involving decomposing living substances, esp. funeral work, sweeping, garbage-collecting, leather-work), possibly also because of a memory of them as originally being subjugated enemy tribes, decried for having first terrorized the Ârya-s and thus ‘deserving’ their reduction to the lowliest occupations. Manu then used this existing contempt in his plea against caste-mixing, by depicting the latter as the cause of the well-known degraded state of the Chandâla-s.

Here, Manu gives in to a typically Brahminical (or intellectuals’) tendency of subjugating reality to neat little models, in this case also with a moralistic dimension. Practice of course is both simpler and more complicated than Manu’s model of caste relations. Low-castes are typically the children of low-castes, not of mixed unions between people of different higher castes. And children of mixed unions do not form new castes, they are accepted into one (usually the lower) of the two parental castes. But Nietzsche is not known to have taken an interest in such historical and sociological detail, neither for its own sake nor for the purpose of giving a verified groundwork to his Manu-based speculations.

2.2. Manu and race

In one respect, Manu’s idea of blaming social disorder on intermarriage seemed attractive to Western readers in the late 19th century, for it agreed with one of the tenets of the flourishing race theories, viz. that race-mixing has a negative effect on the individuals born from such unions. Better a negro than a mulatto, for the latter may have inherited a share of ‘superior’ Caucasian genes, but he will be plagued by an internal conflict between the diverging ‘natures’ of the two parent races. Likewise, the promiscuous servant woman described by Manu may have felt flattered by the interest her Brahmin lover took in her, but for her offspring it would have been better if she had restricted her favours to someone of her own caste. So, a pure low-caste ends up superior to a mixed offspring of high and low castes. While it remains absurd to posit that sweepers and funeral workers (the lowest castes) came into being as children of unions between priests and maidservants, or between the princess and the miller’s son, Manu’s little idea resonated with a cherished belief of Nietzsche’s contemporaries.

In another respect, though, this contrived idea of Manu’s, and Nietzsche’s injudicious acceptance of it, conflicts with 19th -century racial thought. It was then generally believed that the ‘Aryan race’ had invaded India, bringing the Sanskrit language and proto-Vedic religion with them, then subjugated the natives and locked them into the lower rungs of the newly-invented caste system, a kind of apartheid system designed to preserve the Aryan upper castes’ racial purity. (For a critical review of this theory, vide Elst 2007).

In that connection, the reading of varna, ‘colour, social class’, as referring to skin colour, was upheld as proof of the racial basis of caste. To put this false trail of 19th -century race theory to rest, let us observe here that neither the Rg-Veda nor the Manu Smrti connects varna to skin colour. The term varna, ‘colour’, is used here in the sense of ‘one in a spectrum’, just as the alphabet is called varna-mâla, ‘rosary of colours’, metaphor for ‘spectrum (of sounds)’. So, the varna-vyavasthâ is the ‘colour system’, i.e. the ‘spectrum’ of social functions, the role division in society. Just as the existence of social classes in our society doesn’t imply their endogamous separateness, the Vedic varna-s were not defined as endogamous castes.

Physical anthropology has refuted the thesis of caste as racial apartheid long ago (Ghurye 1932), refuted at least according to the scientific standards of the day. Today the science of genetics is fast deepening our knowledge of the biological basis of caste, including the migration history involved in it. As the jury is still out on the genetic verdict, we cannot use that fledgling body of evidence as an argument in either sense here. But the use of colours as a purely symbolical, non-racial marker of social class is attested in several other Indo-European-speaking societies, the closely related Iranian society but also the distant and all-white Nordic class society of jarl (nobleman) with colour white, karl (freeman) red, and thraell (serf) black, as described in the Edda chapter Rigsthula.

In the predominant racialist view of the 19th century, the lowest castes were the pure natives, the highest the pure Aryan invaders, and the intermediate castes the mixed offspring of both. But Manu’s view, though often decried as ‘racist’ in pamphlets, is irreconcilable with this, for it classifies the lowest castes as partially the offspring, even if the sinful offspring, of the highest castes. The caste hierarchy as conceived by him is not a racial apartheid system. As an aspiring historian of caste society, Manu may have been seriously mistaken; but if read properly and not judged from simplifying hearsay, he was not an ideologue of racial hierarchy.

However, though the castes may not have originated as genetically distinct groups, their biological and social separation by endogamy over a number of generations was bound to promote distinctive traits in each. Nietzsche sees Manu’s proposed task as one of ‘breeding no fewer than four races at once’ (TI Improvers 3), each with distinct qualities. As a classicist, Nietzsche was certainly aware of the eugenicist element in Plato’s vision of society and he hints at the similarity with Manu: ‘[…] but even Plato seems to me to be in all main points only a Brahmin’s good pupil’ (letter to Peter Gast, KSA 14.420). As for the medieval European society with its division in endogamous nobility and commoners: ‘The Germanic Middle Ages was geared towards the restoration of the Aryan caste order’ (14[204] 13.386). Indeed:

Medieval organisation looks like a strange groping for winning back those conceptions on which the ancient Indian-Aryan society rested,- but with pessimistic values stemming from racial decadence. (letter to Peter Gast, KSA 14.420)

It was mainly European nostalgics of the ancien régime who got enamoured of the caste system. Yet, the rising tide of modern racism also managed to incorporate its own analysis, unsupported by the Hindu sources, of the Hindu caste ‘apartheid’ as a design to preserve the ‘Aryan race’. Nietzsche remained aloof from that line of discourse.

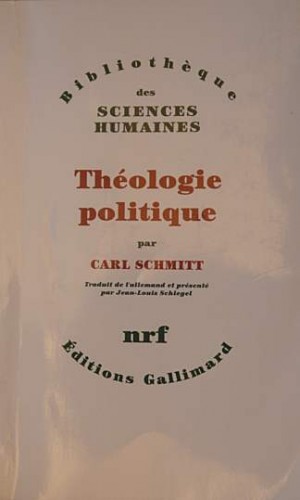

2.3. Manu, priest-craft and legislation

One element in Manu which isn’t easy to fit into Nietzsche’s viewpoint, is his pro-Brahmin bias. On the one hand, Nietzsche couldn’t fail to appreciate the determination of a whole society to set aside resources for a separate caste fully devoted to spiritual and intellectual work. Could a non-caste society have achieved the Brahminical feat of transmitting the Vedas and the ancillary texts and sciences through several thousands of years’ worth of all manner of turmoil? On the other hand, he couldn’t muster much enthusiasm for a system placing the priestly class on top.

Manu is candid and explicit about this: ‘The priest is the lord of the classes because he is pre-eminent, because he is the best by nature, because he maintains the restraints, and because of the pre-eminence of his transformative rituals’ (10.3). In theory, and because it was Brahmins who did all the writing, the Brahmins were the highest caste, and Nietzsche doesn’t seem to question this. But the tangible power in Hindu society lay with the Kshatriya-s, the counterpart of the European aristocracy, which enjoyed Nietzsche’s sympathy far more than any priestly group. For all his sympathy with Manu’s vision, Nietzsche had to criticize Manu’s ‘priest-craft’, debunking it as just a ploy for wresting power:

Critique of Manu’s law-book. The whole book rests on a holy lie: […] Bettering man – whence is this purpose inspired? Whence the concept of the better? We find this type of man, the priestly type that feels itself to be the norm, the peak, the highest expression of humanity: out of itself it takes the concept of the ‘better’. It believes in its superiority, and wants it in fact: the cause of the holy lie is the will to power. (15[45] 13.439)

Nietzsche, however, fails to question Manu’s implicit and explicit claims for Brahminical legislative authority. Through the format of his book, Manu creates an impression (which Nietzsche swallowed whole) that he is laying down a law, but when read more closely, his work proves in fact to be more descriptive than normative, not a law book but rather a treatise on existing social norms and values. ‘Manu prohibits X’ should in most cases be replaced with ‘Manu disapproves of X’ or ‘Manu notes that X is prohibited’. The many contradictions are also quite misplaced in a law book, but perfectly normal in a treatise dealing with the sometimes irregular or conflicting customs in a living society and with ideals versus realities. Moreover, Manu enjoins the ruler to restrain his zeal for law-making and instead respect existing customs in civil society. Manu’s treatise is antirevolutionary, holding off all revolutionary changes whether imposed from above or from below.

Therefore, it bears repeating that Manu with his limited ambitions was not a law-giver gate-crashing into society to impose his own designs. Once caste went out of favour, Manu and the Brahmins were often blamed for having created and imposed the caste system. Yet in fact, as B.R. Ambedkar, a born untouchable who became independent India’s first Law Minister, observed, it was quite outside their power to impose it:

One thing I want to impress upon you is that Manu did not give the law of caste and that he could not do so. Caste existed long before Manu. He was an upholder of it and therefore philosophized about it, but certainly he did not and could not ordain the present order of Hindu Society […] The spread and growth of the caste system is too gigantic a task to be achieved by the power or cunning of an individual or of a class […] The Brahmins may have been guilty of many things, and I dare say they were, but the imposing of the caste system on the non-Brahmin population was beyond their mettle. (Ambedkar 1916 16)

Ambedkar held that castes had evolved from tribes, self-contained communities that maintained their endogamy and distinctness after integrating into a larger more complex society. This continuity has been confirmed from the angle of anthropological research (Ghurye 1959). Nietzsche speaks of the caste system as a grand project of breeding four different nations, but the system simply didn’t come about as the result of a project. Then again, Manu’s choice to preserve and fortify a system already in existence, was also a ‘project’, the alternative being to allow for negligence in caste mores ending in the mixing of castes, of the kind that in the 19th and 20th century started drowning the distinctive identity of the European nobility through intermarriage with the bourgeoisie.

Yet, in other places, Nietzsche drops the idea of a ‘project’ and acknowledges that Manu’s caste scheme is little more than an explicitation and perhaps a radicalization of an entirely natural and spontaneous condition. Like seeks like, people avoid intermarriage with foreigners or with people located much higher or much lower in the social hierarchy, so there is a natural tendency towards endogamy (jâti). Even more natural is the differentiation of social classes (varna) in duties, rights and privileges, i.e social inequality:

The order of castes, the highest and dominant law, is only the sanction of a natural order, a law of nature of the first rank, over which no arbitrariness and no ‘modern idea’ has any power. (AC 57).

In Nietzsche’s books, this counts as a plus for Manu: the Hindu lawgiver didn’t go against the way of the world, whereas Christianity intrinsically militates against nature.

2.4. Jacolliot’s errors

When Nietzsche quotes Manu in his Antichrist and Twilight of the Idols, and in loose notes from the same period (Spring 1888), it is from the French translation by Louis Jacolliot, included in his book Les législateurs religieux, Manou, Moïse, Mahomet (Paris 1876). He says so himself in his letter to Peter Gast. Colli and Montinari remark that ‘the book of Jacolliot about the Indian Law of Manu made a big, indeed exaggerated impression on him’ (6.667).

Jacolliot had served as a magistrate in Chandernagor, a small French colony in Bengal (later he also served in Tahiti), and claimed to have travelled ‘all over India’ in the 27 months he spent in the country. In his attempts at scholarship, he was an amateur and inclined to far-fetched speculations, especially tending to derive any and every philosophy and religion in the world from Indian sources. In his own account, he made his translation with the help of South-Indian pandits. The text from which they worked (and which is apparently lost) was fairly deviant, missing more than half of the standard version, and was apparently already a Tamil translation from Sanskrit. Though his travel stories were very popular among the greater reading public, Jacolliot was not taken seriously by the philologists, finding himself openly denounced as a crackpot by such leading lights as Friedrich Max Müller.

Some parts of Jacolliot’s rendering, including two passages quoted by Nietzsche, do not appear in the standard version of the text. Moreover, in his list of ‘protective measures of Indian morality’ (in TI Improvers 3), Nietzsche makes the additional mistake of quoting as Manu’s text what is in fact a footnote by Jacolliot. This faulty reading is so significant for Nietzsche’s thought that we will consider it separately in §2.5.

Etter notes that until 1987, for a whole century, no Indologist seems to have noticed the textual errors in Nietzsche’s quotations from Manu, though at least Nietzsche’s friend Paul Deussen and later Winternitz (1920) did care to mention Nietzsche’s enthusiasm for Manu. Doniger (1991 xxii), though unaware of Etter’s work, does note a faulty quotation (in Antichrist 56) from Manu 5.130-133, where Nietzsche cites Jacolliot’s non-Manu phrase: ‘Only in the case of a girl is the whole body pure’, as illustration of Manu’s sympathy for women. However, she doesn’t look in a systematic way into the problem of Nietzsche’s source text. This indicates that the eye of the Indologists had not been struck by any serious injustice done to Manu’s message by Nietzsche. Even if the letter of his text was flawed, it did nevertheless carry the gist of Manu’s social vision.

So we shouldn’t make too much of his reliance on a distorted text version, at least in so far as he deals with Manu’s ideology of caste. Indeed, as we shall see, Nietzsche’s faulty understanding of a particularly strange claim made by Jacolliot does not pertain to Manu’s own subject-matter, the caste system, but to a subject entirely outside Manu’s horizon, viz. a supposed role of emigrated Chandâla-s in the genesis of West-Asian religions.

One reason why, in spite of relying on Jacolliot’s flawed translation for quotation purposes, Nietzsche doesn’t do injustice to Manu’s thought, is that he must have been familiar with Manu’s outlook through indirect sources. Indo-European philology was a hot item in 19th century Germany, partly because it had ideological ramifications deemed useful in the political struggles of the day. Indocentrism was most strongly in evidence in Arthur Schopenhauer, a principal influence on Nietzsche. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe had propagated Kâlidâsa’s play Shakuntalâ in Germany. Even G.W.F. Hegel (1826), by no means an Orient-lover, had written a comment on the Bhagavad-Gîtâ, including reflections on the caste system.

So, it is likely that Nietzsche had had a certain exposure to the then-available knowledge of the caste system as outlined by Manu. In particular, he may have already been exposed to Johann Hüttner’s German translation (Die Gesetze des Manu, Weimar 1797, based on William Jones’s English translation, 1796), at least indirectly. If only through his Indologist acquaintances and through general reading, he must have acquired a broad outline of Manu’s caste philosophy.

Nietzsche’s preference for Jacolliot’s over more scholarly Western editions of the MS is a bit of a mystery. He had sufficient training in and practice of philology, as well as philologist acquaintances, to see through Jacolliot’s amateurism. This strange error of judgment remains unexplained, short of the rather sweeping solution of seeing it as a prodrome of his loss of sanity, which befell him only a year later.

2.5. Jacolliot and the Jews

There is one very serious mistake in Jacolliot that seems to have made an important difference to Nietzsche’s thought: his far-fetched speculation that the Chandâla-s left India in 4000 BC (Jacolliot dates the Manu-Smrti itself to 13,300 BC!) and became the Semites. The point here is not the eccentrically early chronology. The exact age of the Vedas was a much-discussed topic, still not entirely resolved, and dating at least the Rg-Veda to beyond 4000 BC, as against Max Müller’s estimate of 1500 to 1200 BC, was not uncommon even among serious scholars like Hermann Jacobi (1894). The point is the alleged Indian and low-caste origin of the ‘Semites’.

Nietzsche hesitates whether to believe Jacolliot on this:

I cannot oversee whether the Semites have not already in very ancient times been in the terrible service of the Hindus: as Chandalas, so that then already certain properties took root in them that belong to the subdued and despised type (like later in Egypt). Later they ennobled themselves, to the extent that they become warriors […] and conquer their own lands and own gods. The Semitic creation of gods coincides historically with their entry into history. (14[190] 13.377f.)

To the ignorant reader, this hypothesis is strengthened considerably by Jacolliot’s additional claim, uncritically quoted in full by Nietzsche (TI Improvers 3, referring to the demeaning features of Chandâla existence enumerated in Manu 10.52), that the Chandâla-s were circumcised. This is based on a mistranslation of daushcharmyam in a verse (MS 11:49) which strictly isn’t about Chandâla-s but about the karmic punishment for the student who has slept with his guru’s wife, either in this or a former lifetime. The mistranslation first appeared in a commentary on Manu by Kullûka from the 13th century, when Northern India had been conquered by Muslims. The word means ‘having a skin defect’ but was reinterpreted as ‘missing skin (on the penis)’, hence ‘circumcised’. The medieval Hindu commentator’s purpose clearly was to classify Muslims as contemptible Chandâla-s. Some Hindu scribes were very conscientious in rendering texts unaltered, others felt it would be helpful for the reader if they updated the old texts a bit, which seems to have happened in this case.

An anomaly in Nietzsche’s reference to male circumcision as an alleged link between the Chandâla-s and the Jews is that he extends the alleged Chandâla observance of ‘the law of the knife’ to ‘the removal of the labia in female children’ (TI Improvers 3). Female circumcision, in origin a pre-Islamic African tradition, is a common practice in some Muslim communities. Among South-Asian Muslims, it is rare but not non-existent. However, it is not a Jewish practice, certainly not among the Ashkenazi Jewish communities Nietzsche knew in Germany, and it is not part of the commandments in Moses’ law. So, his own assumption that the Chandâla-s (with whom Kullûka associated the Muslims) practised female circumcision should have put him on guard against the deduction of a connection with the Jews.

At one point in his unpublished speculations about Manu’s caste rules, Nietzsche actually uses the term ‘circumcised one’ where the context indicates that he means someone at the bottom end of the caste hierarchy:

The killer of a cow should cover himself for three months with the skin of this cow and then spend three months in the service of a cowherd. After that he should make a gift to the Brahmin of ten cows and a bull, or better even, all he possesses: then his fault will have been evened off. He who kills a circumcised one, purifies himself with a simple sacrifice (whereas even killing a mere animal demands a penitence of six months in the forest, unshaven). (14[178] 13.363)

Through Jacolliot’s clumsy translation, this seems to refer to the authentic passage listing the different punishments for killing people belonging to different social classes, as well as for killing different categories of animals (MS 11.109-146). There, for instance, the punishment for killing a member of the servant class is candidly evaluated as rather unimportant: it is fixed at one-sixteenth of the punishment for killing a priest (11.127). Nietzsche’s information that a cow-killer should cover himself with the cow’s skin as part of his penance is also correct (MS 11.109). That killers doing penance should live in the forest unkempt and with matted hair is stipulated in MS 11.129. So, in broad outline, Nietzsche is conveying a genuine tradition. However, this passage from Manu doesn’t specify any particular level of punishment for the case of untouchables, the lowliest subset within the ‘servant’ class. Even conceding that Nietzsche correctly renders Manu’s general intention in allotting only a minimal punishment for the killing of people with minimal standing in the caste hierarchy, the fact remains that the authentic passage contains no reference to ‘skin-defective’ people, let alone to Kullûka’s and Jacolliot’s interpretation of that term, viz. ‘circumcised ones’. But Nietzsche had genuinely interiorized the notion that Indian low-castes in the first century CE were circumcised. In calling them ‘circumcised ones’ off-hand, he treats the alleged circumcision of the Chandâla-s as a given.

Compounding this important mistake, Nietzsche (TI Improvers 3) further quotes from Jacolliot’s Manu version an insertion by the medieval commentator to the effect that the Chandâla-s used a right-to-left script, allegedly because writing from left to right like in the Sanskritic script, and even the use of the right hand, was forbidden to them. Like circumcision, the leftward script is a feature of Muslim culture. But to confuse matters further for Nietzsche, both features are also in evidence among the Jews, whose alphabet has a common origin with the Arabic one. Joining the dots, Nietzsche concludes that: ‘The Jews appear in this context as a Chandala race’, and explains the Jewish people’s alleged priestly leanings from their supposed origins as a class of underlings of the Hindu priestly caste, ‘which learns from its masters the principles by which a priesthood becomes master and organizes society’ (letter to Peter Gast, KSA 14.420).

As an exercise in genealogy, this hypothesis of Nietzsche’s is highly unconvincing. If something is to be explained about the Jews by their purported provenance from specific Indian low-castes, wouldn’t it be more logical, and certainly simpler, to let them continue the cultural features of low-caste life, as is effectively the case with the Gypsies? Conversely, if the Jews had to be of Indian origin and if they were suspected of ‘priest-craft’, shouldn’t they rather be descendents of the Brahmin caste?

The question is all the more poignant when we consider that the idea of a Jewish-Brahmin connection was already quite ancient. In his plea Contra Apionem (1.179) the Jewish-Roman historian Flavius Josephus quotes Aristotle’s pupil Clearchos of Soli as having claimed that Aristotle had been very impressed once with the discourses of a Jewish visitor, and more so with the steadfastness of his dietary discipline, and had concluded that in origin the Jews had been Indian philosophers. A similar claim is found in the Hellenistic-Jewish philosopher Aristoboulos. So, two millennia before Nietzsche, an Indian origin was already ascribed to the Jews. (A Brahminical connection is still attributed to the Jews in today’s India, both by Hindu nationalists who believe everything of value originates in India and invoke the superficial phonetic similarity between ‘Brahma/Saraswati’ and ‘Abraham/Sarah’, and by low-caste activists whose anti-Brahminism borrows the rhetoric of international anti-Semitism, attacking the Brahmins as ‘Jews of India’, e.g. Rajshekar 1983 2.)

Unlike Jacolliot, Nietzsche was interested in Judaism and its purported Chandâla origin mainly as an angle from which to attack Christianity. As Lincoln (1999 110) observes,

he came to be infinitely more critical of Christianity than of Judaism, and he saved some of his most scathing contempt for those (like Wagner, Bernhard Förster, and others of the Bayreuth circle) who were only anti-Semites in the narrowest sense, that is, Christians who failed to realize that everything wrong in Judaism was amplified and exacerbated in Christianity.

So, in Nietzsche’s view, the alleged Chandâla traits, especially resentment against the noble and the successful, though carried over by Judaism, were in fact at their most powerful and noxious in Christianity:

Christianity, which has sprung from Jewish roots and can only be understood as a plant that has come from this soil, represents the counter-movement to every morality of breeding, race or privilege:- it is the anti-Aryan religion par excellence: Christianity the transvaluation of all Aryan values, the victory of Chandala values. (TI Improvers 4)

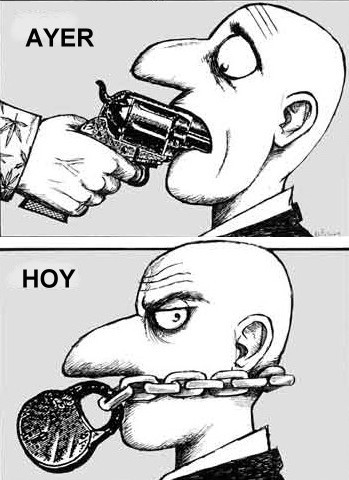

Though not very important in quantity, the Chandâla statements in Nietzsche’s work have made a mark on his whole anthropology, with the Chandâla as the lowest extreme in the range of human diversity. Sentences like the one just quoted corroborated the emerging dichotomy of ‘Jewish’ and ‘Aryan’, which was by no means intrinsic to the concept of ‘Aryan’ even after its somewhat distortive adoption into European languages from Sanskrit. They also helped make Nietzsche’s image as an incorrigible anti-egalitarian who burdened the lower classes with a caste-like inborn inferiority. Even if his anti-egalitarianism was not of the racist or anti-Semitic kind, it was nonetheless in sharp conflict with the rising tide of liberalism and socialism. Any ‘leftist Nietzscheanism’ was thereby forever doomed to a contrived denial or uneasy management of this contradiction between the freedom-loving element in Nietzsche and his condemnation of certain communities to a permanent position of contempt. That is one reason why Monville (2007) speaks of ‘the misery of leftist Nietzscheanism’. As his book’s reviewer in the Belgian Communist Party paper Le Drapeau Rouge (Oct. 2007) sums it up: ‘This German philosopher was openly racist and endowed with a remarkable and odious contempt for the social condition of the losers in the caste struggle.’

2.6. Nietzsche’s errors

Nietzsche has been accused of being very selective in what he retained and quoted from the Manu Smrti, especially its most un-Christian pieces of praise for the female sex, e.g. that all good things including access to heaven ‘depend upon a wife’ (MS 9:28). On that basis, he waxes eloquent about the woman-friendliness of the Hindu sages:

I know no book in which so many gentle and nice things are said to women as in Manu’s law book; these old greybeards and saints have a manner of being kind to women that has perhaps not been outdone. (AC 56)

The quotations are by and large genuine, but ought to be counterbalanced by far less flattering quotations from the same text. Wendy Doniger (1991.xxi) chides Nietzsche for this one-sided representation and quotes Manu (9.17): ‘The bed and the seat, jewellery, lust, anger, crookedness, a malicious nature and bad conduct are what Manu assigned to women.’

However, Nietzsche’s selectiveness doesn’t really misrepresent Manu’s attitude in what was to him the relevant issue, for this much remains true, that Manu genuinely values the role of women as wives and mothers. They were not equal with men (‘It is because a wife obeys her husband that she is exalted in heaven’, 5.155), just like in most other cultures, and Manu too considered them fickle and untrustworthy and what not, but fundamentally they were a very auspicious part of the cosmic order. The good thing about women was not their equality with men, which would have been a ridiculous notion to Manu just as it was to Nietzsche, but that they provided pleasure in life and perpetuated the species. For the same reason, sex is treated in a matter-of-fact manner because even if a delicate subject with problematic ramifications in day-to-day human relations, in essence it is an auspicious cornerstone of the cosmic order. Nietzsche contrasts this with an alleged woman-hating and anti-sexual tendency in Christianity as well as in Buddhism.

On the whole, Nietzsche does justice to Manu’s view of man and society. His main error does not consist in false or mistaken assertions about Manu’s position, only in a limited grasp of the Indian historical context. He was too much in a hurry to enlist Manu in his own ideological agenda to familiarize himself with the actual reality as well as with the philosophical background of caste society.

3. Nietzsche’s use of Manu

To what extent did Nietzsche’s idealized view of Hindu caste society play a role in his views of socio-political matters and of religion?

3.1. Favourable contrasts with Christianity

For Nietzsche, Manu’s vision contrasts favourably with Christianity in several specific respects. Firstly, its goal is not to deform mankind and clip its wings, but to ‘breed’ it, to direct its natural growth and evolution in a certain direction. Consistently with this difference in goals, there is a different approach: while Christianity ‘tames’, Manu ‘breeds’, i.e. he manipulates natural tendencies in a chosen direction. He does not destroy but shapes up. He shows no resentment against the existing order but tries to preserve and ‘improve’ it (AC 56f.).

Secondly, Nietzsche applauds Manu’s candid acceptance and promotion of inequality, which follows naturally from an acceptance of life:

And do not forget the central point, the fundamental difference between it and every type of Bible: it lets the noble classes, the philosophers and warriors, stand above the crowd; noble values everywhere, a feeling of perfection, saying yes to life,- the sun shines over the entire book. All the things that Christianity treated with its unfavourable meanness, procreation for instance, women, marriage, are here treated with seriousness, with respect, with love and trust. How can you really put a book into the hands of children and women when it contains that mean-spirited passage: ‘To avoid fornication, let every man have his own wife and every woman her own husband: it is better to marry than to burn.’ [Paul: 1 Cor.6:2-9 - KE] (AC 56)

Thirdly, he welcomes Manu’s intolerance towards pessimism: even the ugly and lowly are part of the world’s perfection. There is no need to ‘cure’ the world of their presence, they are given a place somewhere in the system.

Fourthly, asceticism is present in Brahmanism as much as in Christianity, but its outlook and motivation is radically different. It does not stem from nor aim at life-denial, it is the joy of the strong who thereby feel and enjoy their strength of character. It is significant that the ascetic tradition originated in the martial Kshatriya caste, to which the Buddha and Mahâvîra Jîna, founders of the surviving ascetic sects of Buddhism and Jainism, belonged by birth. The Indian ascetic’s striving is of the heroic type, seeking to achieve liberation by conquest of the self, not by imprecating divine favours. His celibacy is not a matter of prudery or distrust of sexuality, but of preserving one’s sexual energy and of not diluting masculine standards by symbiosis with women and children.

And whereas these ascetic traditions would still fail to earn Nietzsche’s full approbation because of their hostility to the worldly vale of tears (though their assumption of suffering as the profound nature of all experience might also resonate with the sceptical-pessimist streak in Nietzsche), the Brahminical ascetic tradition as expressed in the Upanishads bases its inner quest on the perception of joy as the intrinsic nature of all experience. According to the Taittiriya Upanishad (2.5), the innermost level of consciousness, underneath the physical, energetic, mental and intellectual ‘sheaths’ covering the Self (âtman), is the sheath consisting of bliss (ânandamaya kosha):

Verily, other than and within that one that consists of understanding [= the intellect – KE] is a self that consists of bliss. […] Pleasure is its head; delight, the right side; great delight, the left side; bliss, the body; Brahma, the lower part, the foundation.

So, the level of consciousness into which the yogi sinks when he stills his thought processes, is one of natural bliss. This illustrates how asceticism as a practice of profound self-mastery need not be based on a sense of tiredness and loathing of the world. The focus in this case is not on the painful experiences from which yoga delivers us, but on the joy which is ever-present and can be awakened further by yoga. To complete this more positive conception of asceticism, Manu does not define the ascetic as one who rejects family and society (the way the Buddha did, or the way Christian monks do), nor as one who spurns normal life for the ascetic life; but as one who completes normal life with an ascetic phase, one who fulfils his social duties first and then, in middle age, crowns his career with the promotion to the ascetic’s lifestyle:

When a man has studied the Veda in accordance with the rules, and begotten sons in accordance with his duty, and sacrificed with sacrifices according to his ability, he may set his mind-and-heart on freedom. (MS 6.36)

Eventually, Nietzsche never got farther than a mere glimpse of this alternative view of asceticism, which contrasts so promisingly with the Christian one of self-punishment. He was locked in his European freethinker’s struggle with the Christian heritage. In the brief months of mental clarity that remained, he didn’t find the time or the appetite to explore the potential help that Hindu thought could have offered him in resolving his very European questions.

3.2. Goddamn this priest-craft

Anything good that may have sprung from Manu has come about thanks to the cunning schemes of Hindu priest-craft, for Nietzsche invariably a vector of the ‘lie’. Given Nietzsche’s views on ‘the uses and drawbacks of truth for life’, the use of this despised priest-craft becomes acceptable because it ends up serving the aims of life rather well. That’s better than the alleged life-denying impact of the Christian lie, but it’s still a lie. Only with that limitation can we say Nietzsche was enthusiastic about Manu.

While Christianity keeps its flock in check with promises and threats of the consequences in the afterlife, Manu achieves the same control with promises and threats of the karmic results in the next incarnations. That at least was and is the common view, and Nietzsche was not sufficiently versed in the subject to know and point out that among Hindu classics, Manu stands out by making only a limited use of the reincarnation doctrine and actually making much more reference to the promise of achieving, or the threat of withholding, access to swarga, ‘heaven’. Numerous times heaven is held up as reward, hell as punishment, only rarely is karma invoked, e.g. an unfaithful wife will be reborn as a jackal (9.30). This afterlife with heaven and hell is the old view of the Vedas, where the heroes go to some kind of exuberant paradise, the way the Greek warriors went to the Elysean Fields, the Germanic ones to the Walhalla, or the Islamic jihâd fighters to Jannat where numerous houri-s (nymphs) shower them with their attentions. By contrast, the notion of reincarnation was a later Upanishadic and Shramanic (i.e. monastic, principally Jain and Buddhist) innovation. Both views of the hereafter get mixed up in Manu, e.g. the punishment for perjury is that the culprit is ‘helplessly bound fast by Varuna’s ropes for a hundred births’ (8.82, meaning he will suffer dropsy during that many incarnations, vide Doniger 1991 160), but also that he ‘goes headlong to hell in blind darkness’ (8.94).

From Nietzsche’s distant viewpoint, however, this made little difference, for either way, priests were exploiting supernatural beliefs about people’s invisible fate after death to impose their law on their people: ‘Reduction of human motives to fear of punishment and hope for reward: viz. for the law that has both in its hand’ (14[203] 13.385).

In this respect, Nietzsche classifies Manu along with Moses, Confucius, Plato, Mohammed as just another religious law-giver, i.e. an immoral liar who tricked his society into a certain morality by means of a pious fantasy. They were all the same, e.g.: ‘Mohammedanism has learned it again from the Christians: the use of the hereafter as organ of punishment’ (14[204] 13.386).

It is the way of priests to present the mos maiorum, or whichever innovation they wanted to introduce into it, as divinely revealed:

A law book like that of Manu comes about in the same way as every book of law: it summarizes the experience, shrewdness and experiments in morality of many centuries, it draws a conclusion, nothing more. (AC 57)

To prevent further experimentation by communities affirming their human autonomy,

a double wall is set up […]: first, revelation, that is the claim that the reason behind the law is not of human provenance, has not been slowly and painstakingly looked for and discovered, but instead has a divine origin, [arriving] whole, complete, without history, a gift, a miracle, simply communicated… And second tradition, that is the claim that the law has existed from time immemorial, that it is irreverent to cast doubt on it, a crime against the ancestors. The authority of the law is founded upon the theses: God gave it, the ancestors lived it. (AC 57)

Therefore, Nietzsche rejects a certain anti-Semitic rhetoric then common in ex-Christian circles, and pleads that in this respect, the Aryan Manu is no better than the Semitic Bible, whose priestly vision actually had Aryan origins:

There is a lot of talk nowadays about the Semitic spirit of the New Testament: but what one calls by that name is merely priestly,- and in the Aryan law book of the purest kind, in Manu, this type of ‘Semitism’, i.e. priestly spirit, is worse than anywhere. The development of the Jewish priestly state is not original: they got to know the blueprint in Babylon: the blueprint is Aryan. If the same returned to dominate again in Europe, under the impact of the Germanic blood, then it was in conformity with the spirit of the ruling race: a great atavism. (14[204] 13.386)

Once, in an unpublished note, Nietzsche expresses a healthy modern scepticism towards the pious caste order with its touch-me-not-ism:

[…] the Chandala-s must have had the intelligence and the more interesting side of things to themselves. They were the only ones who had access to the true source of knowledge, the empirical. Add to this the inbreeding of the castes. (14[203] 13.386)

So, to the modern man Nietzsche, the uptight purity rules against inter-caste contact and the distance which the upper castes kept from activities that would get their hands dirty, remains too stifling for comfort. While generally inclined towards the aristocratic system, he did not want to spend his energies campaigning against class- or race-mixing, unlike many Europeans and Americans during the century preceding 1945. Indeed, his ‘genealogical’ speculations largely aimed at disentangling the different components of Europe’s culture and value system, for he was fully aware of the mixed character of the European civilization and nations. In the caste system, he admired the elitist spirit, but not to the extend of trying to uphold its obsessive purity rules in modern society. And while caste ensured stability, a condition cherished by priestly types, Nietzsche was temperamentally more favourable to scenarios of upheaval. In that respect, the modern world was more congenial to him than medieval European or ancient Indian hierarchies, which he preferred to admire from a comfortable distance.

3.3. The racism Nietzsche didn’t borrow from Manu

In Nietzsche’s day, racism was a fully accepted and even dominant paradigm. Nietzsche himself was not its champion or its mastermind, but neither did he stand as a rock against the racially-inclined spirit of the times. The term ‘race’ had a wider range of meanings then, from ‘family’, ‘clan’ and ‘nation’ to phenotypical ‘race’ to the ‘human race’ (exactly the range of meaning that jâti has in colloquial Hindi). In Nietzsche’s case, it only rarely seems to have the fully biological sense that was gaining ground then:

His not infrequent use of the expressions ‘classes’ and ‘estates’ along with ‘races’ strengthens the suspicion that Nietzsche saw the ‘Aryans’ and ‘Semites’ in the first place as social units, rather as ‘peoples’ or societal ranks, less as ‘races’ in the modern sense. They are what they are because they have lived in specific ‘environments’ for a long time. (Schank 2000 60)

Nietzsche shows some knowledge of the findings of Indo-European philology, especially the theories about the wanderings of the ‘Aryans’ and the resultant substratum effect of pre-Indo-European native languages on the language of the Indo-European settlers (Schank 2000 54). Thus, non-Indo-European roots borrowed from lost substratum languages account for nearly 30% of the core vocabulary in Germanic and nearly 40% in Greek, and the differentiation of Proto-Indo-European into its daughter languages is partly due to the respective impact of different substratum languages on its dialects. Nietzsche fully accepted the then-common view that the native Europeans had adopted their Indo-European languages from tribes immigrating from the East, an Urheimat located anywhere between Ukraine and Afghanistan.

Early in the 19th century, this line of research originally had a fairly Indocentric focus, with India itself being the favourite Urheimat, but as India’s status declined from a mystical wonderland to just another colony, the preferred homeland moved westward. The quest for the early history of Indo-European was interdisciplinary avant la lettre in that it brought proto-sociological insights into its historical-linguistic speculations. Thus, what is now called the ‘elite dominance’ model of language spread, in which the dominant Indo-Europeans imparted their language to the substratum populations, included considerations of the caste system.

The Hindu caste system was widely interpreted in racial terms, viz. apartheid between Aryan conquerors and pre-Aryan natives. Likewise, the situation of the Greeks in Greece, with a vocabulary including numerous pre-Indo-European loanwords and the coexistence of free Greeks with a lower class of helots and slaves, was commonly understood as reflecting the subjugation of a native race by the superior invading Aryan race. Nietzsche accepted this racial scenario to an extent in the case of Europe, but most remarkably did not apply this paradigm to Indian society. Adopting Manu’s view, he saw the difference between high and low castes as not being one between superior and inferior races, but between pure and mixed lineages: ‘good proper marriages bring forth good children; a bad one, bad ones’ (14[202] 13.385). To Manu, good marriages are endogamous marriages, e.g. a marriage between two low-caste people is good.

It is only in a very loose sense of the term that Manu could still be described as a racist, viz. in the sense that he did derive people’s rights from the kinship group to which they belonged. These groups need not be distinguished by phenotypical traits, as races in the modern conception are, but just like races they are communities to which one belongs through birth. That is why recent UN campaigns against racism have tended to include casteism as a peculiar case of racism.

Where Nietzsche did (unsystematically) espouse ideas that were later incorporated in the prevalent racist discourse, he definitely didn’t get them from Manu. Thus, the notion of the ‘blonde Bestie’, which, according to Lincoln (1999 104 ff.), cannot be uncoupled from racial thought, has nothing whatsoever in common with Manu’s view of mankind. Firstly, Nietzsche goes along with the then-common identification of ‘Aryan’ with ‘blond’, as when he speaks of ‘the blond, that is Aryan, conqueror-race’ (GM I 5). This idea was totally unknown to Manu, who may well never have seen a blond person in his life yet lived in the centre of what he called Ârya society. But let us add that Nietzsche doesn’t go all the way in this identification of blondness with superiority, for in the same paragraph he goes on to include the warrior aristocracies from Arabia and Japan.

Secondly, Nietzsche’s glorification of the unbridled norm-breaking wildness as a privilege of the conquerors and ruling class, personified as the ‘blond beast’, is without parallel in Manu or the other masterminds of Hindu civilization. In Nietzschean terms, Manu stands for the ‘Apollinian’ values of order, balance, clarity and stability, not at all for the disruptive ‘Dionysian’ exuberance of the ‘blond beast’.

3.4. The antisemitism Nietzsche didn’t borrow from Manu

Nietzsche did not posit a simple division of the world’s religions in two categories, such as ‘Abrahamic’ vs. ‘Pagan’. Even in typologically similar and genealogically related religions, he sees the opposition between deeper psychological tendencies. Thus, both the ‘Aryan’ and the ‘Semitic’ religions show the same division in ‘yes-saying’ and ‘no-saying’ attitudes:

What a yes-saying Aryan religion, born from the ruling classes, looks like: Manu’s law-book. What a yes-saying Semitic religion, born from the ruling classes, looks like: Mohammed’s law-book, the Old Testament in its older parts. What a no-saying Semitic religion, born from the oppressed classes, looks like: the New Testament, in Indian-Aryan terms a Chandala religion. What a no-saying Aryan religion, grown up among the ruling classes, looks like: Buddhism. It is perfectly in order that we have no religion of oppressed Aryan races, for that would be a contradiction: a lordly race is either on top on going extinct. (14[195] 13.380f.)

Note that his judgment of the Jewish Old Testament, with its wars and love stories, is less negative than that of the Christian New Testament. Not that he failed to share some of the common opinions about the Jews, e.g. that they are only middlemen, not creators: ‘The Jews here also seem to me merely “intermediaries”/“middlemen”, – they don’t invent anything’ (KSA 14.420). He also seems to have seconded the ancient view that the Jews were motivated by hatred of the rest of mankind: